On October 4th I received an email from a Wall Street Journal reporter who wanted my thoughts on a study about “bot-marketing of e-cigarettes” for a story he was planning.

I figured this was about a recent report from the British company Astroscreen, who told Wired UK that they discovered a “coordinated, inauthentic social media campaign has been explicitly targeting key U.S. policymakers in an attempt to force them to withdraw plans for anti-vaping legislation.” Ironically, Astroscreen had built a bot to do their work for them, and because the bot is “proprietary machine learning technology” (translation: no one but the authors can see how or why they came to their conclusions), there is really no way to judge the validity of their conclusions.

I was prepared to discuss this with the reporter who contacted me. But he wasn’t contacting me about the Astroscreen bot study.

The WSJ reporter wanted comments on a different report, by unnamed researchers at the Public Good Projects (PGP) and funded by something called the Nicholson Foundation. When I said I was uncomfortable commenting on a study I hadn’t seen or read about yet, the reporter offered to send me the report on the condition that I not share or comment on it until after the story ran. I agreed to those terms.

Let me point out how odd it is that two distinct private organizations decided to “expose” apparently rampant “bot” activity in the vaping advocacy space by leaking unvetted “studies” to major news outlets, apparently without any plans to get those studies peer reviewed, and prior to any public release.

When I read the PGP report, I noticed other similarities. Like Astroscreen, PGP was inexcusably opaque about their methodologies. According to PGP, their analysis offers “never-before-seen information on the role that bots are currently playing in online conversation around e-cigarettes and tobacco products.” Specifically, they conclude that “over half of all messages transmitted through public media sources in the United States regarding e-cigarettes and tobacco products may be posted by automated accounts, or bots.”

Yet they don’t provide any useful information on how they arrived at such a conclusion. Readers are just supposed to trust that the finding is valid. But I noticed something in the report that gave me good reason not to trust it. And, since the article the Wall Street Journal eventually published included none of my comments to the reporter, I will explain them here.

However, before I get to that, let’s look at some of the broader problems with PGP’s report.

What do they mean by “bot” anyway?

First of all, PGP is inexcusably vague about what they actually did, how they did it, and what they actually found. And this makes it very hard to interpret statements that seem straightforward in the report, like this one: "out of a total sample of 2,536,659 Twitter messages related to e-cigarettes or tobacco, 22.6% of messages were posted by humans, 20.8% posted by suspected bots, and 56.6% are confirmed to have been generated by bots."

It’s impossible to meaningfully interpret the above statistic because we don’t know what PGP means by bots. Or rather, we don’t know what they counted as a bot when they did the analysis. We do know, from how the report is framed, that PGP wants us to think about bots in vaping as automated accounts, designed to appear to be human, that operate to spread misinformation about nicotine and e-cigarettes, and/or advertise them to anyone and everyone, especially kids.

But what PGP wants us to think about when we hear “bot” is not the same as what they actually counted as a bot in this study. So how did PGP actually identify bots, and what did they consider to be a bot? Here’s what they say in the report:

“PGP is able to identify which posts have a high likelihood of originating from bots and which have a high likelihood of originating from humans…. PGP researchers examine multiple account characteristics to determine the likelihood of a post being from a bot, including (but not limited to) the frequency and timing of posts, the number of posts, the number of followers, and engagement with other accounts. Bots, particularly those created with malicious intent, are incredibly nuanced and are often designed to appear exactly like a human. Therefore, a simple examination of basic account and profile characteristics is insufficient to gauge the likelihood of automation.”

This is useless. I don’t really care how accurate PGP thinks their methods are; I want to make that evaluation myself, and I can’t based on the information they provide. But all they want to give me is this patronizing and overly vague excuse for not telling me what they actually looked at, so I can judge for myself if their study is valid. They treat their methods as magic and frame them as too sophisticated for their readers to understand, which is basically a huge red flag.

PGP shared some post-hoc clarifications on Twitter yesterday about their classification process and methodology that were even more vague and meaningless than what they said in the actual report. For example: “We define “automation" as a score from 1-100. A 100% robot will do things like auto-RT, posting no original content.”

Peter Sterne, a freelance journalist who writes about the media industry, succinctly articulated the problem with PGP’s bot definition in a private message to me: “PGP has apparently adopted an absurdly broad definition of bot (anyone who uses any auto-posting app) that sweeps up lots of real people, while strongly implying that all “bots” are part of a sophisticated social media operation and their tweets can’t be taken at face value.”

In any event, PGP was obviously interested in studying bots, however they’ve defined them. The proportion of bots active in the vaping space, and the role they may play in advocacy is a legitimate research puzzle, and I think a lot of vapers would find a study that could answer these questions pretty interesting. But the thing is, PGP didn’t design a study that could answer the questions motivating their report.

If PGP wanted to understand the characteristics of accounts in a particular population of tweeters (i.e., vapers) they would need to figure out a way to get a representative sample of accounts from that population. This is virtually impossible, but that’s beside the point because PGP doesn’t even appear to understand that they would need to do something like this at all. PGP didn’t sample accounts, they sampled tweets. These tweets were sent by accounts (obviously) so they did end up with a collection of accounts, but it was completely inappropriate for the researchers to proceed to make inferences about the population of accounts who tweet about vaping on the basis of some accounts whose tweets happened to end up in their sample.

The other big problem with the report is that it doesn’t actually say how many unique accounts they are talking about here. They report numbers of tweets (probably because those numbers are bigger, and PGP wants to impress us), but we don’t know how many accounts are sending them. And this actually matters a lot if there are any real bots in the sample (and there probably are some) because an obscure spam-bot with zero followers programmed to tweet hundreds of times per day about vaping could have generated a disproportionate number of the tweets in the whole sample, even if the bot has little to no effect beyond its tiny isolated bubble.

These bots are not bots at all

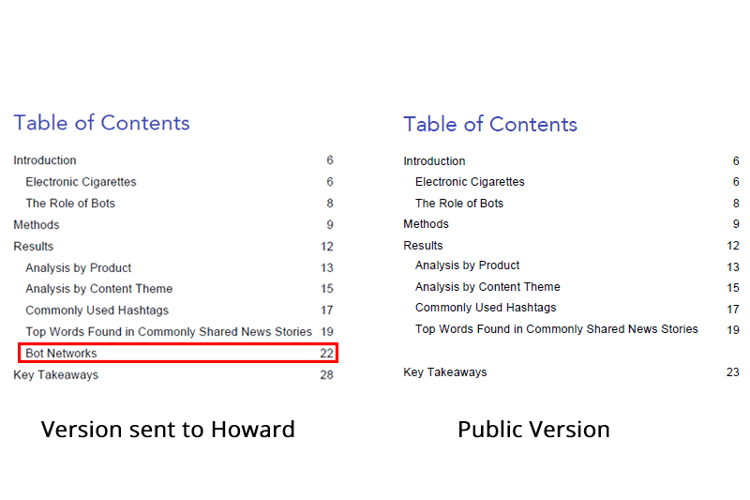

The lack of transparency, absent definitions, and clear methodological incompetence are reason enough to suspect the conclusions of this study. But the concrete indicator that PGP’s findings aren’t valid is a section of the report that was deleted prior to its public release. (You can see the public version on PGP’s website.)

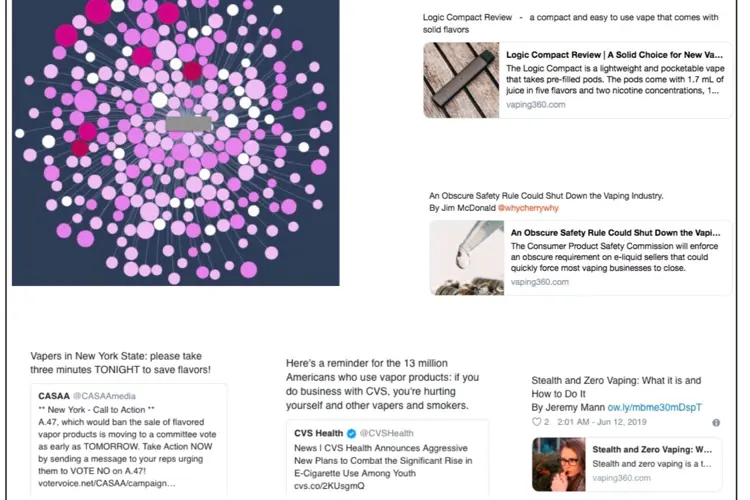

Back to the Wall Street Journal. When they asked me to comment on the PGP report, they sent me a copy. It was 32 pages long. The results section was 15 pages long. And a subsection within the results, titled “Bot Networks,” occupied about 40 percent of these results. It consisted of five “micro-level” analyses of so called “bot accounts” and their “bot networks identified throughout [PGP’s] analysis process.” They use graphs to represent each network. (Here is the version I was given by the reporter.)

Each of PGP’s graphs were built around a focal node, representing a “bot” in the PGP analysis. That node was linked to other nodes representing accounts that retweeted the so-called bot’s tweet. Social network analysts refer to these graphical representations as “ego networks,” because they depict the relationship between a central node (the “ego”) and connected nodes (“alters”). PGP color coded the alter nodes according to whether they met their undisclosed criteria for being a bot, with white nodes representing accounts determined to be humans. White nodes were the minority of nodes in all of PGP’s networks.

PGP wants us to believe that the vast majority of Twitter activity on vaping is probably not generated by real human beings. They redacted the name of the “ego” bot at the center of each botnet. Why? In the report they claim this was to protect the privacy of the accounts, but if the accounts are bots why does this matter?

Frankly, even if PGP actually was interested in guarding the identities of bot accounts disguised as real people who are meddling in on-line vaping discourse with potentially dire consequences for public health (or so they say), the fact of the matter is that they did a terrible job.

I was able to easily identify the specific accounts represented as the center node in each of the five supposed bot networks PGP included in their original report. I was able to do this because PGP included screenshots of tweets from the accounts that anyone could type into the search bar in the Twitter user interface and retrieve. I did that for the tweets of each account, checked their follower and post count with what PGP reported, and verified who all of them were. The entire process took me less than half an hour. And guess what? None of these accounts are “bots posing as real humans.”

Out of the five accounts PGP chose for their exemplary bot networks discussion, there was only one that I didn’t recognize. It was a commercial account based in the U.K., using Twitter to advertise its eBay listings for various products, including e-liquid and CBD. Did the account appear to use automation to post tweets? Yup. Was there any indication that people weren’t behind those tweets? No. Would any reasonable person mistake this for anything other than an online commerce company’s commercial account? No. Was there any indication that the account was promoting beyond its own follower network? No.

As for the four accounts I was familiar with, three were private accounts by individuals who are, longtime vaping advocates, and quite obviously real people. The other was the Twitter account for this very publication. Vaping360 news editor Jim McDonald manages and tweets from this account, and Jim is not a bot.

So of the five supposed bots: one is the account for a vaping publication that is run by one of the journalists who uses it to post articles, and engage with other tweeters (so he posts original content). Three are private individuals who advocate for vaping. And the other one is some British retailer. It is extremely difficult for me to believe that anyone familiar with any of these accounts would conclude that they are bots posing as humans. Or businesses posing as individual humans. Or businesses using bots to pose as individual humans. Or anyone involved in any nefarious activity, for that matter.

And this makes PGP’s decision to redact the names of these five accounts a bit suspect. First of all, surely they knew that it would be possible for someone who wanted to know who the accounts were to figure it out with the information they made available. So they didn’t protect anyone’s privacy, they just made it slightly more laborious for someone who wanted to know the identity of the accounts to find that information.

The screenshots I was able to use to search tweets from these accounts included retweets and replies to the accounts from “alters” who are also not bots—and no measures were taken to protect the identities of these accounts. PGP’s screenshots revealed the names and handles of other accounts in the so-called “botnets,” just not the central bots (who are not bots).

All of this makes it hard for me to believe that protecting the privacy of the “bots” was the main reason PGP hid the account IDs. It doesn’t make sense because the protections were extremely easy for anyone to subvert, because the protections weren’t extended to the accounts appearing in screen shots, and because at the end of the day, PGP had a far greater incentive to hide this information for their own protection and to protect the credibility of their flawed report than anything else.

Protecting privacy or saving face?

I would like to know why PGP published a different version of the report from the one they shared with the Wall Street Journal. Apparently so did Gregory Conley, who asked them to account for this choice on Twitter. PGP’s answer to him was this:

“The WSJ had an exclusive on the research and we shared info during due diligence. At one point we shared 5 accounts that had high automation scores, out of the 1 million+ messages analyzed. We didn't want those accounts targeted. So neither the article or report mentions them.”

PGP seems to be implying here that the botnets were provided to the Wall Street Journal as additional context to the final study. If the analysis I flagged as fatally flawed was actually never intended for public consumption, and simply some additional material sent to the Journal along with the official report, that does not change the fact that it undermines the validity of the entire study.

But it is pretty hard to believe they didn’t intend to have this in the final version. The section was listed in the table of contents of the version of the report that was sent to me. This was a core part of their results section, with the “botnets” framed as illustrative of the abstract phenomenon they claimed their report illuminated. There was no indication that this content was not intended to be a major part of the final report.

I was given the impression that what I was given was the final report, and when I flagged this analysis as grossly flawed (and unethical) I was never told that it was a cursory part of the study or special to the Wall Street Journal. While I can’t say for certain, the reporter who sent it to me seemed to be under the impression that this was the final version as well. And really, who would send the working draft of a ground-breaking report to a newspaper you’re offering an exclusive to? That doesn’t really make sense. The document that included the now-deleted botnet analysis was polished, the deleted section was part of the table of contents, nothing indicates that this was not intended to be the final product.

If PGP found out how badly they had bungled this analysis, it should have caused them to question the validity of their entire study. The responsible, intellectually honest, and transparent thing to do here would be to ask the newspaper to hold or cancel their story so the report could be fixed, or perhaps if the flaws were so serious, abandoned. At the very least, some note should have been made indicating that the version sent to the Journal was different than the final version published on the website.

I think PGP removed those pages once they understood the obviousness of the grave errors they made. They subverted normal scientific processes in all other respects of this work. Why should I—why should anyone—believe that they cared about anything other than saving face? If PGP has any actual concrete evidence to support their claim that the decision to cut this section was unrelated to the fact that their botnets were not actually botnets, they should come forward with that.

Dehumanizing legitimate protesters

PGP’s report paints a picture of a sophisticated network of bots designed to fool people into believing they’re individual humans in order to manipulate discourse on vaping. The fact that none of their best examples had any of the characteristics of this type of account (and four of them were humans I actually happened to know) raises serious questions about the reliability of the entire enterprise.

The vaping advocacy sphere on Twitter is a loosely connected community of individual citizens who are using their mostly private social media accounts in a specific context. These people are not on Twitter for the benefit of opportunistic “public health monitoring and communication” researchers, who have something to gain by harvesting their user-generated content and presenting it out of context in order to illustrate a wildly implausible and intellectually dishonest theory that influential vape advocates are nothing more than a sophisticated network of malicious bots, duplicitously posing as humans in order to spread misinformation in the interest of some nameless, faceless, corporate power.

I’m not sure whether the apparent dishonesty that saturates the PGP report represents the organization’s attempt to fool the public, or is more reflective of the fact that they’ve fooled themselves.

But it doesn’t matter. With or without the deleted “botnets” section, PGP’s report is wholly unethical. This report was not about contributing to knowledge on vaping advocacy, it was about creating a media frenzy around a shocking finding that isn’t actually real. It was carried out by a private, unnamed group of market researchers who either do not understand or do not care about the norms of transparent, valid and reliable scientific work. They also ignored the very real power imbalance between the people who do research on vaping tweeters, and the real people who use Twitter to advocate for vaping.

The PGP report is propaganda aimed at dehumanizing legitimate protesters, discrediting their cause, and censoring their speech on social media platforms. The report was presented with the veneer of science, but it is wholly intended to serve political ends.

Suggested further reading:

- The Association of Internet Researchers, Ethical decision making

- Clive Bates, Memo to public health grandees: vaping, vapers and you

- Jathan Sadowski, Companies are making money from our personal data – but at what cost?

The Freemax REXA PRO and REXA SMART are highly advanced pod vapes, offering seemingly endless features, beautiful touchscreens, and new DUOMAX pods.

The OXVA XLIM Pro 2 DNA is powered by a custom-made Evolv DNA chipset, offering a Replay function and dry hit protection. Read our review to find out more.

The SKE Bar is a 2 mL replaceable pod vape with a 500 mAh battery, a 1.2-ohm mesh coil, and 35 flavors to choose from in 2% nicotine.

Because of declining cigarette sales, state governments in the U.S. and countries around the world are looking to vapor products as a new source of tax revenue.

The legal age to buy e-cigarettes and other vaping products varies around the world. The United States recently changed the legal minimum sales age to 21.

A list of vaping product flavor bans and online sales bans in the United States, and sales and possession bans in other countries.