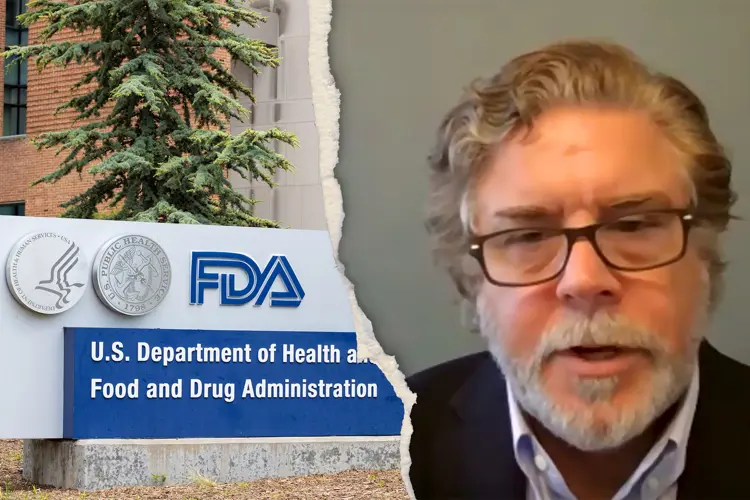

On Monday, lawyers representing the FDA and vape manufacturer Triton Distributionfaced off in the Supreme Court, taking questions from the court’s nine justices. The FDA is seeking to overturn a Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals decision that found FDA marketing denial orders (MDOs) issued to Triton and Vapetasia were “arbitrary and capricious” and violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).

A full transcript of the proceedings is available on the Supreme Court website.

For just over an hour the opposing attorneys—Deputy Solicitor General Curtis Gannon representing the FDA, and Eric Heyer on behalf of Triton—took turns fielding questions about whether the FDA had given clear requirements to manufacturers submitting premarket tobacco applications (PMTAs), and whether the agency had moved the goalposts after the fact when it denied millions of products without the individual assessments mandated in the Tobacco Control Act, which governs the FDA’s regulatory processes.

The Tobacco Control Act says the FDA must assess whether a product is “appropriate for the protection of public health”—a vague standard that gives the agency wide latitude to interpret. Triton argued that one element of the FDA’s denials—a requirement to show that non-tobacco-flavored vape products are comparatively more effective than tobacco-flavored ones—was introduced after the fact, as was a requirement that successful applications must include evidence from certain kinds of long-term studies.

The FDA had never said those studies were the only possible acceptable evidence, argued Gannon; it had merely said they would "likely" be needed.

Lawyers point out that the justices could assign more or less weight to topics discussed in oral arguments---or not depend on them at all in their decision. Issues not discussed could even form a primary basis for the court’s final ruling.

The FDA, said Triton, had also claimed before applications were submitted that marketing plans (which would show how the company intended to avoid youth uptake) would be an important PMTA component. But the agency never even reviewed Triton’s plans before issuing an MDO. The FDA contended that, if ignoring marketing plans was an error at all, it was “harmless error” that could be either ignored or remedied by remanding the applications back to the agency to review marketing plans only.

The study requirement and marketing plan “switcheroos,” as one Fifth Circuit judge described them, were the major topic of discussion during the arguments. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito seemed to lean into the argument that the FDA didn’t provide “fair notice,” with Thomas calling FDA guidance “a moving target.”

But overall, the justices seemed somewhat sympathetic to the FDA’s defense that it had not changed its position on required evidence. The agency had said such studies weren’t required, said Gannon, but made clear that some strong evidence would be needed to prove products would benefit the population as a whole.

The three liberal justices—Elena Kagan, Kentanji Brown Jackson, and Sonia Sotomayor—were clearly satisfied with the FDA’s actions, and even conservative Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch seemed to question whether Triton had made its fair notice case.

Kavanaugh also suggested that applicants who receive MDOs can simply reapply. Triton attorney Heyer reminded him that waiting two or three more years for another FDA decision while unable to do business would mean bankruptcy for Triton and many other companies, who would no longer be protected from FDA enforcement until receiving FDA authorization.

Indeed this would be no problem for a company like Altria, which could sell cigarettes while it waits for an FDA authorization for its vaping products. But Triton doesn’t sell cigarettes. (Altria, by the way, helped write the Tobacco Control Act, which deliberately sets a high bar for approval of low-risk cigarette alternatives.)

The Tobacco Control Act says the FDA must assess whether a product is “appropriate for the protection of public health”---a vague standard that gives the agency wide latitude to interpret.

While it’s difficult to predict the outcome of the case from the arguments (especially for a non-lawyer like me), it must be noted that some major issues were not discussed much or at all, including the Tobacco Control Act itself and the “appropriate for the protection of public health” standard, whether the FDA’s new de facto standards for flavored products should have been handled with APA-mandated notice-and-comment rulemaking, and how the Supreme Court’s new decision rejecting court deference to agencies making rules based on vague statutes would apply to the Triton case.

Lawyers point out that the justices could assign more or less weight to topics discussed in oral arguments—or not depend on them at all in their decision. Issues not discussed could even form a primary basis for the court’s final ruling.

Many vape industry and consumer advocates seem mystified because the conservative justices did not—as we were led to expect by some—use the opportunity to rain down fire and brimstone on the FDA, but instead seemed rather bored and disinterested in the agency's actions. Why? Nobody knows. At least four of the justices proactively chose to hear this case, so some members of the court clearly feel strongly about it for some reason. It would be difficult to believe any of the six conservative justices would lobby for the chance to decide a case in favor of the hated administrative state—but stranger things have happened.

We’ll have to wait until next year—perhaps as late as June—to find out what the justices are thinking and what they decide. Meanwhile, a new administration will take over, and the FDA and Justice Department could be given new marching orders on vaping regulation and enforcement. President-elect Donald Trump promised during the election campaign that he would “save flavored vaping.” Now is his chance.

While most of the discussion Monday tackled technical legal points, there were also comments illustrating that some members of the court have no idea of what vaping products are or how they work—which is not at all comforting to consumers who depend on these products.

“Blueberry vapes are very appealing to 16-year-olds,” said Justice Kagan, “not to 40-year-olds.”

The Freemax REXA PRO and REXA SMART are highly advanced pod vapes, offering seemingly endless features, beautiful touchscreens, and new DUOMAX pods.

The OXVA XLIM Pro 2 DNA is powered by a custom-made Evolv DNA chipset, offering a Replay function and dry hit protection. Read our review to find out more.

The SKE Bar is a 2 mL replaceable pod vape with a 500 mAh battery, a 1.2-ohm mesh coil, and 35 flavors to choose from in 2% nicotine.

Because of declining cigarette sales, state governments in the U.S. and countries around the world are looking to vapor products as a new source of tax revenue.

The legal age to buy e-cigarettes and other vaping products varies around the world. The United States recently changed the legal minimum sales age to 21.

A list of vaping product flavor bans and online sales bans in the United States, and sales and possession bans in other countries.